The Allstate Corporation ($ALL): Deconstructing the Balance Sheet and Market Hype

The Machine in the Ghost: Deconstructing Allstate's Two Realities

On the surface, The Allstate Corporation is a paragon of financial stability. A glance at its recent performance reveals a company firing on all cylinders. In its last quarterly report, it posted earnings per share of $5.94, absolutely crushing analyst consensus estimates of $3.20. That’s not just a beat; it’s a demolition. The stock enjoys a "Moderate Buy" rating (an average across 19 analysts), with price targets stretching towards $250. Its price-to-earnings-growth ratio sits at an attractive 0.70, suggesting its growth isn't even fully priced in yet.

This is the Allstate you see on a stock ticker, the one discussed in earnings calls. It’s a clean, efficient, number-crunching enterprise. The Zacks industry report places the Property and Casualty (P&C) sector in the top 15% of all industries, citing prudent underwriting and exposure growth as key drivers. Allstate is a leader in this prosperous pack, a well-oiled machine converting premiums into profit with remarkable efficiency. The company’s four-quarter average earnings surprise was a staggering 57.7%—to be more exact, 57.7%. Hedge funds and institutional investors own 76.47% of the company's stock for a reason. They see a predictable, profitable operation.

But that’s only one side of the ledger. While the financial statements present a world of order and predictable growth, the company's own communications reveal the chaotic, messy, and deeply human world it actually operates in. The machine, it turns out, runs on the unpredictable fuel of human behavior and misfortune. And I've looked at hundreds of these corporate profiles, and the contrast between Allstate's sterile financial reporting and its raw operational data is particularly stark.

What does it mean when a company's success is so directly correlated with its ability to price danger? And is the polished financial narrative telling the whole story of the risks simmering underneath?

From Balance Sheet to Blacktop

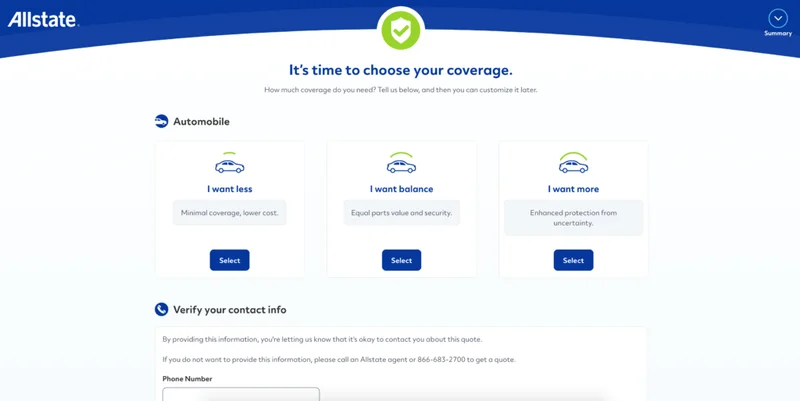

Let’s pivot from the Wall Street view to the street-level view—literally. A few days ago, Allstate reveals America's 10 riskiest roads for drivers this Halloween. It’s framed as a public service announcement, a friendly reminder from the "Good Hands" people. But read between the lines, and it’s a raw look at the company’s core business model. They aren’t just warning you about risk; they are showing you their work.

The report pinpoints segments like I-8 East in San Diego and I-240 East in Memphis, using data from its Drivewise telematics program. It identifies the exact times when hard braking (a deceleration of 8+ mph in one second) and speeding (15+ mph over the limit) are most frequent. Imagine the scene: the sudden lurch you feel on Phoenix’s I-17 North near exit 223B on a Saturday afternoon as someone realizes they're about to miss their turn. That single, visceral moment of panic is a data point. Allstate has millions of them. This isn't just a safety warning; it's a window into the raw material that feeds their underwriting algorithms. The company’s profit margin is built on the statistical probability of that hard brake turning into a collision.

This brings up a critical methodological question. The data comes from Drivewise users, people who have voluntarily agreed to have their driving monitored in exchange for potential discounts. Are these drivers representative of the general population? I’d argue they are not. The very act of opting into a surveillance program suggests a higher degree of conscientiousness. This is a classic sampling bias. If these are the "risky" behaviors exhibited by a self-selected group of presumably safer-than-average drivers, what does the data for the entire driving population actually look like? The reality is likely far more chaotic.

This operational messiness isn't just confined to the highways. It plays out in courtrooms, too. Judge rules Allstate owes TD $143,500 in underinsured motorist coverage battle. In the context of Allstate's $50.95 billion market cap, this amount is a rounding error. It’s financially insignificant. But narratively, it’s crucial. It represents the constant, grinding friction inherent in their business. Their product is a promise, a complex legal document that is perpetually tested, debated, and litigated. Every single day, somewhere, Allstate is in a dispute over what its promise actually means. This isn't a failure of the system; it is the system.

A Tale of Two Ledgers

So, we are left with two conflicting portraits of the same company. One is a clean, predictable financial powerhouse, celebrated by analysts for its efficiency and robust earnings. The other is a company immersed in the unpredictable, high-friction world of human risk—analyzing dangerous roads, battling in court over policy language, and underwriting the potential for catastrophe. The disconnect is jarring. The machine is only pristine because its fuel is so messy. The company's success isn't just about managing risk; it's about profiting from a world that seems to be getting riskier, whether through more severe weather events or simply a moment of distraction on a busy interstate. The question for any long-term observer isn't whether Allstate is profitable now, but whether the models pricing the chaos can keep up with the chaos itself.

- Search

- Recently Published

-

- Duke Energy: What's Really Going On?

- Value City Furniture: Are they finally going out of business? The bankruptcy talk.

- Scott Bessent: Who Is This Guy, The Trump Whispers, And What Are They Not Telling Us?

- American Signature Files Chapter 11: What Happened?

- Tesla Ride-Hail in Arizona: What This Means for the Future of Mobility

- OECD: What it is, and its AI Data Focus

- Nebius: Stock, Coreweave, & Nvidia – What's the Real Deal?

- Bitcoin: Beyond the Headlines, What This Moment Truly Signals

- Social Security Retirement: The Realities of Your Payouts and How to Plan

- Starlink Satellites: How Many Are Really Up There, Where They're Hiding, & What's The Actual Point?

- Tag list

-

- carbon trading (2)

- financial innovation (2)

- blockchain technology (2)

- carbon tokens (2)

- Blockchain (11)

- Decentralization (5)

- Smart Contracts (4)

- Cryptocurrency (26)

- DeFi (5)

- Bitcoin (29)

- Trump (5)

- Ethereum (8)

- Pudgy Penguins (5)

- NFT (5)

- Solana (7)

- cryptocurrency (6)

- XRP (3)

- Airdrop (3)

- MicroStrategy (3)

- Stablecoin (3)

- Digital Assets (3)

- PENGU (3)

- Aster (8)

- Zcash (6)

- iren stock (3)