JPMorgan's Next Move: What Their Latest Report Reveals About the Future of Money

I want you to look past the numbers for a moment.

Yes, JPMorgan Chase, the largest bank in the United States, just posted a staggering $14.4 billion profit for the third quarter. That’s a 12% jump from last year, a full billion dollars more than the sharpest minds on Wall Street even thought possible. By every traditional metric, this should have been a victory lap. A day of champagne corks and soaring stock charts.

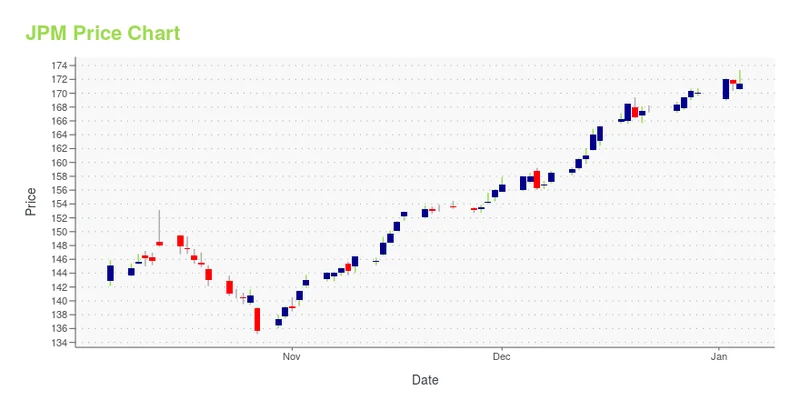

Instead, the bank’s stock price stumbled.

And right there, in that strange disconnect—between spectacular success and market anxiety—lies a far more interesting story. It’s not a story about finance. It’s a story about information, transparency, and the messy, beautiful, and absolutely essential role of human judgment in a world increasingly run by machines. This isn't just an earnings report; it's a glimpse into the operating system of the future.

The Cockroach in the Code

Let’s break down the mechanics. The profit engine was firing on all cylinders. The investment banking division, the high-stakes world of corporate dealmaking, saw its revenue surge 17%. The trading desks, where fortunes are made in the flicker of a screen, pulled in a massive $8.94 billion, a 25% leap. These are the kinds of numbers that build empires.

But buried in the fine print was a bug. A $170 million charge-off.

A charge-off—in simpler terms, it's a debt the bank has given up on ever collecting—was linked to a subprime auto lender called Tricolor Holdings. Tricolor, which specialized in loans to borrowers with poor credit, went bankrupt in September amid allegations of fraud. It was a relatively small loss for a behemoth like JPMorgan, a rounding error on a multi-trillion-dollar balance sheet. But it wasn't the number that mattered. It was the nature of the problem.

And then came the quote from CEO Jamie Dimon. Instead of downplaying it, he leaned right in. "It is not our finest moment," he admitted, with a frankness that feels almost alien in the polished world of corporate-speak. Then he delivered the line that sent a shiver through the market: "When you see one cockroach, there's probably more."

When I first read that "cockroach" line, I didn't see a banker admitting defeat. I saw an engineer pointing to a potential stress fracture in a bridge before it collapses. He wasn't just reporting a past error; he was issuing a real-time diagnostic on the health of the entire system. He was telling the world that the complexity of modern finance means that even with the best risk models and the most powerful computers, things can—and will—go wrong. And that honesty, that willingness to flag a systemic vulnerability? That’s not a weakness. It’s the most powerful feature you can build into any complex system.

The Human Algorithm

This act of radical transparency didn't stop with one bad loan. Dimon zoomed out, using the earnings call as a platform to issue a much broader warning. He pointed to "significant risks" on the horizon: trade uncertainty, worsening geopolitical conditions, and, most pointedly, asset prices that "look like they're entering bubble territory."

This is where things get truly fascinating. In an era dominated by high-frequency trading algorithms that make decisions in nanoseconds based on pure quantitative data, Dimon was acting as a kind of "human algorithm." He was processing a completely different dataset—one composed of geopolitical tension, political sentiment, and that intangible, unquantifiable feeling that things are getting too hot. He was providing the qualitative override, the common-sense check that a machine simply can't.

It’s like the dawn of the aviation age. Early pilots had their instruments—altimeters, speedometers—but they also flew by the "seat of their pants," using intuition and feel to navigate turbulence the gauges couldn't predict. Dimon is piloting this colossal institution through a global economy of unprecedented complexity, and he's telling us he feels a tremor that doesn't yet show up on the dashboard. We're talking about a system so interconnected that a trade dispute in one corner of the globe can ripple through supply chains and hit a subprime auto lender in Dallas, and the ability to see that chain of events before it fully breaks is the new form of genius.

So, what does it mean when the market sells off a stock after the company posts record profits? It means the market is listening. It’s pricing in the warning from the human at the controls. It’s reacting not just to the data of the past three months, but to the wisdom about the next twelve. And that, I would argue, is an incredibly healthy, incredibly advanced sign. It’s a system learning to value foresight as much as it values profit.

What if this became the new gold standard for leadership? What if we demanded this kind of proactive transparency not just from our bankers, but from our technologists, our politicians, and our scientists? Could we build more resilient, more antifragile systems if we celebrated leaders for finding the "cockroaches" early, rather than for pretending their code is perfect?

The Currency of the Future is Trust

In the end, the stock dip wasn't a sign of failure. It was the sign of a system working exactly as it should. It was a market rewarding honesty with attention, and pricing in the nuance of a complex reality. The story of JPMorgan's third quarter isn't the $14.4 billion. It's the incalculable value of a leader willing to say, "It is not our finest moment," and in doing so, making the entire system smarter, safer, and more prepared for what comes next. In a world drowning in data, that kind of candid, human-led course correction isn't just a feature. It's everything.

- Search

- Recently Published

-

- Duke Energy: What's Really Going On?

- Value City Furniture: Are they finally going out of business? The bankruptcy talk.

- Scott Bessent: Who Is This Guy, The Trump Whispers, And What Are They Not Telling Us?

- American Signature Files Chapter 11: What Happened?

- Tesla Ride-Hail in Arizona: What This Means for the Future of Mobility

- OECD: What it is, and its AI Data Focus

- Nebius: Stock, Coreweave, & Nvidia – What's the Real Deal?

- Bitcoin: Beyond the Headlines, What This Moment Truly Signals

- Social Security Retirement: The Realities of Your Payouts and How to Plan

- Starlink Satellites: How Many Are Really Up There, Where They're Hiding, & What's The Actual Point?

- Tag list

-

- carbon trading (2)

- financial innovation (2)

- blockchain technology (2)

- carbon tokens (2)

- Blockchain (11)

- Decentralization (5)

- Smart Contracts (4)

- Cryptocurrency (26)

- DeFi (5)

- Bitcoin (29)

- Trump (5)

- Ethereum (8)

- Pudgy Penguins (5)

- NFT (5)

- Solana (7)

- cryptocurrency (6)

- XRP (3)

- Airdrop (3)

- MicroStrategy (3)

- Stablecoin (3)

- Digital Assets (3)

- PENGU (3)

- Aster (8)

- Zcash (6)

- iren stock (3)